In the world of evolutionary biology, few concepts are as fundamental—and as misunderstood—as speciering. This term, often used in scientific circles, refers to the process by which new species arise from existing ones. While it may sound like a technical term reserved for textbooks, speciering lies at the heart of how life on Earth has diversified into millions of unique forms. From the finches of the Galápagos Islands to the ever-evolving strains of viruses, speciering is both a timeless natural phenomenon and a current biological reality.

In this in-depth article, we’ll unpack the meaning of speciering, examine the mechanisms that drive it, explore real-world examples, and consider its broader implications in science, ecology, and even conservation. Whether you’re a biology student, science educator, or just a curious mind, this guide will equip you with a complete understanding of how species come into being.

What Does Speciering Mean?

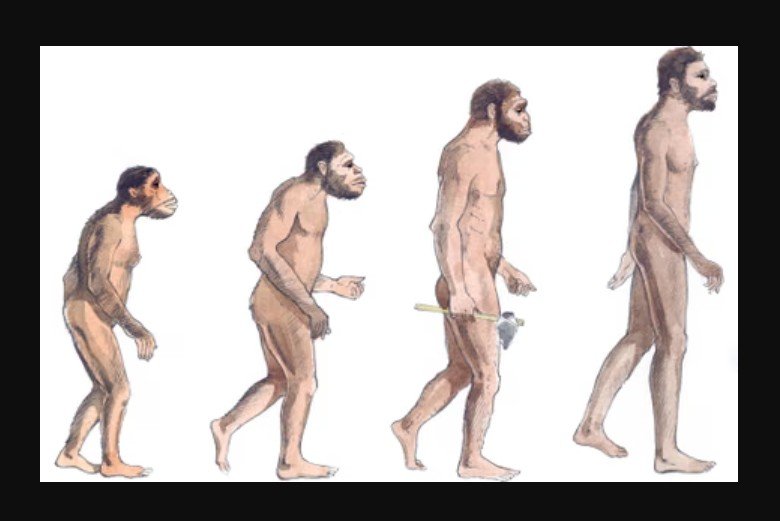

Speciering, often used interchangeably with speciation, is the evolutionary process through which populations evolve to become distinct species. At its core, it involves the splitting of one lineage into two or more genetically independent ones. These lineages then diverge over time through the accumulation of genetic changes, eventually becoming reproductively isolated.

Reproductive isolation is the key criterion for defining a species under the biological species concept. This means that once two populations can no longer interbreed and produce fertile offspring, they are considered distinct species.

The term speciering is rooted in evolutionary theory and is deeply associated with the ideas presented by Charles Darwin, particularly in On the Origin of Species where he emphasized gradual divergence through natural selection.

The Biology Behind Speciering

To understand how speciering works, it’s essential to look at the mechanisms that drive it. Evolutionary biologists generally classify speciation into several types based on how geographic and reproductive barriers arise.

Allopatric Speciering

This is the most common form and occurs when a population is divided by a physical barrier—such as a mountain range, river, or ocean. Over time, the two isolated populations experience different environmental pressures, mutations, and selection forces. Eventually, they become so genetically distinct that interbreeding is no longer possible.

One of the most cited examples of allopatric speciering is the case of the Darwin’s finches in the Galápagos Islands. Geographic isolation led to the evolution of multiple bird species from a common ancestor, each adapted to a different ecological niche.

Sympatric Speciering

Sympatric speciation occurs without physical separation. Instead, species diverge while inhabiting the same geographic region. This often happens due to ecological specialization, such as adapting to different food sources or mating preferences.

Insects like apple maggot flies have demonstrated sympatric speciation. Populations originally feeding on hawthorn trees began infesting apples after their introduction to North America, eventually leading to reproductive isolation.

Parapatric and Peripatric Speciering

These are less common forms. Parapatric speciering happens when populations are partially isolated and only occasionally interbreed. Peripatric speciering occurs when a small group breaks off from a larger population, often at the edge of the range, leading to rapid divergence due to genetic drift and founder effects.

Genetic Drivers of Speciering

Understanding the genetic mechanisms behind speciering is crucial to appreciating how new species emerge. These mechanisms include:

- Mutation: Random changes in DNA that introduce genetic variation.

- Natural selection: Traits that confer survival or reproductive advantages become more common.

- Genetic drift: Random fluctuations in allele frequencies, especially significant in small populations.

- Gene flow reduction: Limiting the exchange of genetic material between populations leads to divergence.

Over many generations, these forces result in populations accumulating enough genetic differences to prevent successful interbreeding, finalizing the speciering process.

Real-World Examples of Speciering in Action

To better grasp how speciering plays out in nature, it’s helpful to look at concrete examples across different taxa.

Cichlid Fish in African Lakes

The cichlid fishes of East Africa’s Lake Victoria, Lake Malawi, and Lake Tanganyika represent one of the most dramatic cases of rapid speciering. Hundreds of distinct species have evolved in relatively short evolutionary time frames. Differences in jaw shape, coloration, and behavior contributed to reproductive isolation.

Ring Species

Ring species provide compelling evidence of ongoing speciering’s. In these scenarios, neighboring populations can interbreed with close neighbors but not with populations at the other end of the distribution. The Ensatina salamander in California exemplifies this, showing how gradual divergence can result in eventual reproductive isolation.

Insects and Polyploidy

Some plant and insect species undergo instantaneous speciering through polyploidy, where an organism gains one or more extra sets of chromosomes. This is common in plants and has been observed in some insects, creating new species in a single generation.

Speciering and Evolutionary Theory

Speciering is not an isolated phenomenon but a central mechanism within the broader framework of evolutionary theory. It provides a mechanism for the origin of biodiversity and supports the idea of common ancestry.

Phylogenetics, the study of evolutionary relationships, relies heavily on the results of speciering. Every branch on a phylogenetic tree represents a speciation event—a point where one species splits into two or more.

The rate of speciering varies. Some lineages, like coelacanths, show evolutionary stasis over millions of years, while others, such as Hawaiian drosophilids, diversify rapidly.

Human Impact on Speciering

Human activity can accelerate, slow, or reverse speciering. Habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change can disrupt natural processes, leading to extinctions before speciation can occur. Conversely, human actions can sometimes inadvertently promote speciation.

For instance, urban environments create new selective pressures. Species like city-dwelling mosquitoes have evolved distinct behaviors and genetic profiles compared to their rural counterparts, an early signal of potential speciation.

Hybrid zones are also increasing due to human-induced habitat changes, where species that were once separated are now interbreeding. While this sometimes leads to the collapse of species boundaries, it can also spark new hybrid species.

Speciering and Conservation Biology

Understanding speciering is crucial for conservation efforts. Protecting evolutionary potential—the capacity of populations to adapt and diverge—is as important as preserving current biodiversity.

Conservationists now use evolutionarily significant units (ESUs) to recognize genetically distinct populations that may represent early stages of speciation. This ensures that these populations receive appropriate protection even before they become fully recognized species.

In highly fragmented habitats, preventing genetic bottlenecks and maintaining gene flow can influence whether or not speciering’s occurs. In some cases, conservation may aim to promote speciering as a tool for restoring ecosystems.

Common Misconceptions About Speciering

Many people mistakenly believe that speciering is a rare or slow process. While it often takes thousands or millions of years, it can happen much faster under strong selective pressures, especially in organisms with short generation times.

Another misconception is that speciering always results in better or more complex organisms. In truth, evolution is not goal-directed. Speciering’s produces organisms that are better adapted to their local environments, not necessarily more advanced.

Finally, some assume that species are fixed and immutable. In reality, species are fluid evolutionary units, and speciering is an ongoing, dynamic process.

Why Speciering Matters

The process of speciering isn’t just an academic curiosity—it’s central to many real-world issues. Understanding how species arise informs:

- Drug development by tracking bacterial evolution and resistance.

- Agriculture, where new pests and pathogens emerge through speciation.

- Public health, especially in studying virus mutation and zoonotic jumps.

- Climate adaptation strategies, helping predict which species might survive or evolve in a changing world.

It also enriches our understanding of life’s complexity. Every living thing—from the smallest microbe to the largest mammal—owes its existence to a long chain of speciation events.

Conclusion: The Ever-Unfolding Story of Life

Speciering is more than just a mechanism of change—it’s the engine behind the vast tapestry of life on Earth. By understanding how species emerge, adapt, and diversify, we gain critical insight into biology’s most fundamental processes. From guiding conservation strategies to illuminating our own evolutionary past, speciering connects us to the broader story of life.

As science continues to unravel the genetic and ecological intricacies of speciering’s, our understanding of the natural world—and our place in it—will only deepen. Whether through slow divergence across millennia or rapid adaptation in a few generations, speciering’s ensures that life is always changing, always evolving.

FAQs About Speciering’s

What is the difference between speciering and evolution?

Speciering is a specific outcome of the evolutionary process, leading to the formation of new species. Evolution includes all genetic changes over time, not just speciation.

How long does speciering take?

It varies. Some species take millions of years to diverge, while others—especially microbes—can speciate in a matter of years or decades.

Can humans cause speciering?

Yes, both intentionally (through selective breeding) and unintentionally (via habitat modification, pollution, and climate change).

Is speciering’s reversible?

In rare cases, hybridization or environmental changes can lead to the merging of species, but once reproductive isolation is complete, reversal is unlikely.

Why is speciering’s important for biodiversity?

It’s the primary mechanism by which new species emerge, making it essential to the expansion and resilience of ecosystems.